Herein, we give a detailed post mortem of how the 2010’s formula to building online-native product brands has been progressively hollowed out in pursuit of quicker profits, stripped apart by cancel culture, and today is no longer holding water.

In contrast, we detail the garden3d playbook to building brands. Our partners, clients, and own properties consistently apply human-centric logic to build proud, ethical institutions with multi-generational appeal and longevity by nourishing their every human touchpoint.

RIP: The 2010’s Brand Formula

Synonymous with “Direct to Consumer” (DTC), the millennial formula for online brands was born out of a ~vaguely~ utopian, indie rock post-Occupy mindset of the early 2010s. We couldn’t trust the big banks, and by extension, we couldn’t trust the big brands either. So we decided to build our own brands instead.

These DTC founders were optimistic and rebellious — Obama was our first Black president, and we designed the first bamboo toothbrush you could buy over HTTP(S). The meteoric rise of Shopify and Stripe leveraged that same energy to build their monopolies. Touting empowerment, freedom and accessibility, these now-tech giants sold the American dream back to bright-eyed entrepreneurs, and we (the designers and developers that platformed brands onto these tools) enjoyed hefty salaries and healthy day rates.

The promise of the movement was simple — wielding the power of platform automation, small product lines, focused demographics, a small upstart product (See: Warby Parker, Allbirds, Haus) could play to hyper-individualism while masquerading as “doing better” (apparently) through efficient, nimble and less wasteful processes.

The creative agencies (garden3d included) rode this wave by giving the tin man a heart, repackaging mid-century references or cutesty graphic treatments (unpleasant minimalism) pre-linked with quality and coziness — this became the Millennial Aesthetic.

Millennials inherited Gen X’s allergy to selling out, but couldn’t help seeing dollar signs as they grew up with the internet. We propped up the product as an aspirational ideal, rejected megacorps, and told the world we were doing it better with ~small batch artisanal~ products.

The Millennial Formula held until around 2020 when we were forced inside, advertising on our timelines hitting a bloated and critical mass, becoming oversaturated and fast-redundant as brands failed to differentiate themselves in a sea of the like, crumbling one by one.

Contributing largely to its downfall was the deeply cynical Gen Z consumer. Presenting as a gatekept niche internet product can’t work on a demographic that understand they can know anything with a few keystrokes. On Gen Z’s internet, no gates will hold. Knowing things does not make you special.

As millennial brands struggled to continue presenting as cutting edge and future-forward, the financially nihilistic Gen Z embraced selling out completely, centering personality and identity instead. Personal brands have no overhead, so why bother making a product? They saw through DTC’s thinly veiled authenticity, and compounding with TikTok virality and thirst for attention, the younger generation quickly became a brutal new consumer watchdog, building their personal brands by cancelling and boycotting the those of the generation previous.

The darlings of the movement didn’t make good on their promises, posting losses and fast losing relevance and market share. Knix settled for $1.4M in a marketing class action lawsuit after claiming their products didn’t include PFAs (they did), and Warby Parker recently settled with the state of Kentucky after violating state consumer protection statutes with their online vision tests (you need a real optometrist to prescribe your glasses?).

Struggling to adapt to the changing tide, but hoping to keep the same quality of life afforded by the DTC boom, those same bushy tailed millennials gave up and sold out completely, finally accepting a job in big tech / fashion, or switching to scam industries like big pharma or drop-shipping. Pharmaceuticals, supplements and sexual health have been largely insulated by weaponizing hypochondria and selling snake oil to an anxious, downwardly mobile (and increasingly uninsured) populous.

So now branding erection pills, supplements, and drop-shipped products, those millennials okay with selling out completely were able to continue doing what they’ve always done: Repackaging something we already had and selling it back to us at a higher price point, weaponizing design language to tout the same (flimsy) promise of convenience and quality.

Cynical Consumerism

Today, we watch frozen in horror as environmental protections and basic human rights are stripped away not in rash acts of violence, but extremist acts of legislation. We shrug away pangs of guilt as we dispose of yet another Amazon box. We diligently separate our recyclables and watch meekly as our municipality throws it all in the same truck.

Our Hulu ads and disgraced Youtubers are selling us off-label nootropics and EMF shielding amulets, as AI-generated influencers further beat the dead horse of Alibaba arbitrage.

American trust-the-market logic falsely believes that we can vote for product innovation with our wallets, but whistleblowers and Netflix documentaries have made clear we’re largely animated to buy what’s thrust in front of our dopamine receptors.

But the decision to add to cart is no longer just a mid-scroll knee-jerk reaction. It’s also a risky energetic investment made by an increasingly burnt-out user. The objects in our homes aren’t symbols of good taste; they’re a political track record (I say as someone who once owned a Boring Company cap, shudder). No one wants to be on the wrong side of history.

“Not only do they purchase products that demonstrate their social or political beliefs, but a whopping two in three have boycotted a company they previously purchased from because of its stance on an issue.

And it’s not just the marketing and advertising that comes under scrutiny. More and more, governance is playing a significant role in reputation, brand perceptions and now – purchase decisions. CEO and senior executive salaries have long been under scrutiny, but now, so are their values, actions and beliefs.”

→ In the face of such powerful skepticism and exhaustion, how can we hope to build a brand that people actually like?

Enter Expansive Branding

By contrast — garden3d builds brands that accept their place in society as a type of public and cultural institution, operating with a simple aim of forever expanding to bolster and support its every human touchpoint. They’re open, demonstrative businesses that care for a diverse spectrum of expanding needs and concerns, acknowledging the responsibility that comes with the privilege of employing others and making a profit.

An Expansive Brand does not need to be a B-Corp, charity or non-profit. The logic described herein is intended for profitable and sellable entities. Adopting and investing in expansive brand principles separates the organization from their competition, building leagues of super fans and loyalists through authenticity, dedication, and candor.

To today’s jaded customer, these brands do not take for granted their right to exist. Rather they accept the obligation that comes with the damage and pollution they create by continually offering a substantive and cogent justification to their community for why they deserve to exist at all.

A brand is a boundary that interacts with people. Traditional business logic primarily considers the human touch points that can be most readily understood on a profit and loss statement. Some are obvious: price, look and feel, function, design language, shopping experience.

Cultural intersections that don’t obviously correlate with a brand’s financial growth (historically discarded by the market) include environmentalism, social responsibility, transparency, charitable giving, community-first action, and more.

So rather than the traditional object-oriented approach of wrapping a consumer around a product, we instead aim to identify every opportunity to establish a brand as a public-serving social structure that consistently fortifies an ethical and moral foundation from which to exist.

Every day, our organization aims to offer an updated, legible answer to the most prescient and urgent question of today’s new consumer: “Hey [Brand], why are you even here?”

“The logic of lifestyle is inverting. The lifestyle era was not about creating culture. It was about attaching brands onto existing cultural contexts. It was not about shaping people, it was about sorting consumer demographics into niche categories. But this new cultural economy actually reverses this. For some companies, culture has become the product itself, and the goods have become secondary to the production of culture.”

Substantive Environmentalism

In the wake of the IPCC’s AR6, rampant climate guilt has made consumers acutely aware that buying products makes them complicit in climate change. Today we are in the middle of a global climate uprising, giving rise to a cultural shift whereby consumers are outright demanding meaningful environmental action from brands.

“This study found that, on average, 3 in 5 (64%) consumers say products branded environmentally sustainable or socially responsible made up at least half of their last purchase. And this figure is even higher in India (75%) and China (76%).

What’s more, roughly half (49%) of consumers globally say they paid an average premium of 59% for products branded as sustainable or socially responsible, signaling that consumers are willing to support sustainability with their wallets.

And it’s not just wealthy people who are willing to spend more for sustainability. 4 out of 10 (43%) consumers in the lower income bracket also say they paid a premium for sustainable or socially responsible products. That figure jumps above 60% in China and India.”

— IBM Institute for Business Value, 2022 Balancing sustainability and profitability

The default consumer stance is to assume sustainability initiatives are greenwashing (until proven innocent). It is unhelpful (even regressive) to slap a carbon offset Shopify App on your checkout and call it a day; this simply doesn’t fundamentally move the needle for consumers.

Rather, a substantive, holistic and (most importantly) transparent approach to learning and mitigating environmental risk is necessary for consumers to take notice.

Last year, we proved out this thesis with a $10k USD ad spend on Instagram, showing clearly that substantive sustainability messaging drives up click through rates (CTR) for basically all demographics:

Sadly, a history of expensive consultants accessible only to multinational conglomerates (and miscellaneous conjecture) have led founders to think that rigorous environmentalism is off limits.

Rather, working with Seaborne to build a Lifecycle Analysis (LCA) for a product line can take as little as 40-120 billable hours (roughly the cost of hiring a copywriter or producing a small photo shoot), equipping the team with opportunities and insights to disclose their current environmental standing, improve their design and manufacturing process, and set clear and actionable goals in the open.

What’s more, equipped with carbon footprints and other quantified environmental impact, the business can then make real steps toward climate action and long term environmental improvements.

Take Seed, for example, (raising $40 million last year) who are carbon negative, and open-sourced their sustainable packaging approach, Blueland, aiming to show that sustainable products can be the norm (not the exception), or Mill (a garden3d partner), who’ve raised $70 million to build a sophisticated system of circular economy, helping people living in dense urban areas convert their food scraps.

Employer Responsibility

Working is a political act, and by extension, so too is being an employer.

Today’s companies are founded on a worldwide system of inequality and prejudice. Under the long shadow of colonialism (and other such -isms), and during 2022’s realtime violation and erosion of human rights (by our very own US Supreme Court), today’s younger demographics can no longer stand by organizations complicit in shirking the responsibilities of upholding worker protections.

“When Basecamp CEO Jason Fried announced a number of policy changes, including that there would be “no more societal and political discussions on our company Basecamp account,” about one third of its employees resigned within a matter of days, pressuring Fried to issue an apology.”

As with environmentalism, a brand that is honest and candid about how they’re addressing Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) builds trust with their workers, consumers and stakeholders with a mature, open dialogue and feedback loop.

Companies that go further, awarding ownership fairly by demonstrating a commitment to improving the upward mobility of their people benefit from a dedicated and highly productive team: In 2019, Managed By Q was acquired for $220 million just three years after it distributed 5% of company ownership to its handymen, cleaners and technicians.

Transparency & Aesthetic Honesty

In the shadow of peak millennial brand saturation, “too much design” becomes a telltale sign of a potential attempt to mislead the consumer. Rather, design language should convey an understanding by the brand that their product is not perfect, because it is a response to an ever-changing world. It should not mislead, manipulate, or make promises the product can’t keep.

Open source is an example of such aesthetic honesty. A dedication to the public domain demonstrates that the brand exists to contribute to culture, rather than extract from it. Further, transparency and open source is a request for public input; admonishing hubris in the idea that a small group of people could ever successfully design something for the masses alone.

By releasing intellectual property or sharing trade secrets, a brand is saying out loud:

Its work is a contribution to culture (existing for a greater good)

It is not perfect or magical and will never be finished (but is down to learn in the open)

It wants its community’s input (the product will be better for it)

Take Nuggs (raising $50 million in 2021), who started a changelog as they improve their vegan chicken nuggets in the open, (a candid demonstration that their recipe is not perfect and never finished), or Floyd, who are acknowledging their design is so simple they’ll ship you the basic components so you can make it yourself.

Organic Basics have even gone as far as to publish their Fuck-Ups to show their customers how they’re learning and growing in real-time.

Charitable Giving & Activism

Present in adages like “silence is violence,” a brand that pretends to exist outside of the ongoing cultural context abdicates responsibility from the very society it aims to extract profit from.

Instead, organizations that respond in realtime to global events (with meaningful financial contribution) to fight oppression, support volunteers, and protect humans and ecosystems build leagues of loyalists and advocates.

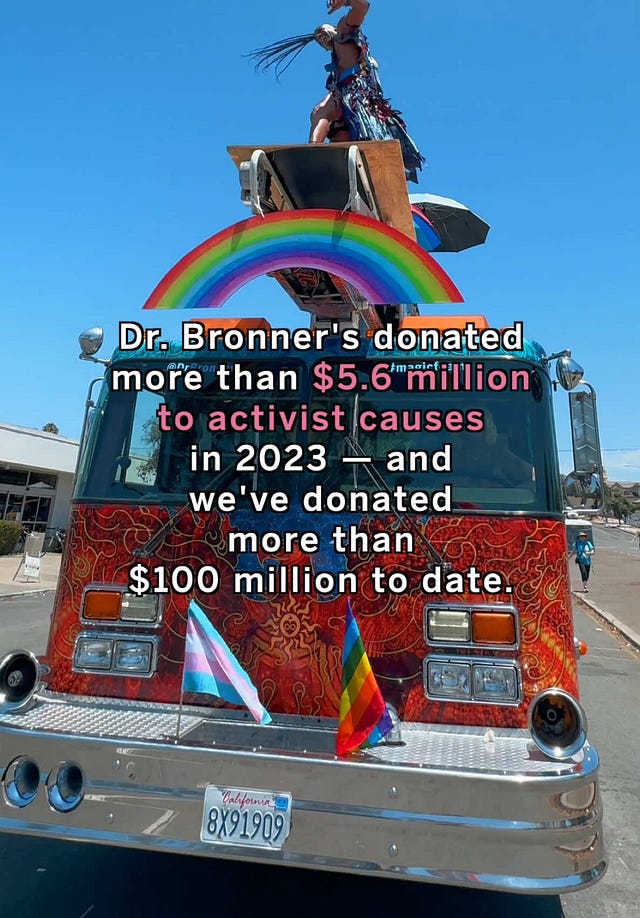

Take Dr. Bronners, who use activism (literally suing the DEA) in lieu of advertising, or Dame Products who sued the MTA for sexism. Following suit, garden3d has recently introduced a charitable giving program, donating ~$63k in the last few years.

“But for all of this star-studded success, Dr. Bronner's hasn't paid a penny — that's right, their advertising budget is zero. They don't pursue celebrity endorsements, or shell out for advertising in the form of television commercials, magazine ads, billboards, or posters. Instead, the brand prefers to spend their revenues on activism.”

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

Community-First Action

Even online brands have a locality — even if that’s internet local. There is always a human being in a physical location on the other end of the tube, and garden3d believes that it has a core responsibility to create safety and spaces for those people to gather, exist, share experiences and build collective power.

A product that exists to help humans regain control and power over their lives is the Light Phone (another garden3d partner), widely heralded for the device’s hardline anti-tech philosophy that consistently leads to happier, calmer, less addicted / anxious, present cell phone users.

Another example of this community first action was garden3d’s decision to build Index — an online and IRL network of spaces to facilitate peer-led programming and learning.

There is a (flawed) prevailing logic that a founder should first find stable and consistent profitability before “doing good.” This thinly-veiled defense of no-holds-barred profiteering still holds court as common founder adage. Our take doesn’t feel particularly radical to us… we simply feel that deprioritizing ethical business practices directly undermines stability, profitability and growth: a death wish for young brands.

Consumer logic has changed, and the online brands of the 2010s that have failed to show an adequate attention to substantive or meaningful causes are reckoning with their unsteady foundation. By contrast, the businesses that have historically stitched an ethical framework into their brand DNA are thriving in this pessimistic climate, as critical consumers take less risks under today’s rising cultural stakes

If you’re building a brand, and you’d like to work with us, please reach out at hello@garden3d.net

Brain buzzing with inspiration after this read. Been thinking about our immense agency as creatives in shaping the future...thanks for the thoughtful analysis as ever.