Since its inception, the corporate sustainability space has been defined by largely voluntary initiatives done in pursuit of marketing objectives. Its reputation is image before impact. Government regulations alongside a budding ‘ESG’ movement have helped to spur a minimum baseline of responsibility, but meaningful action has been pursued only by a minority of outlier companies interested in attracting a consumer who has the eye and conscience for ethicality. It’s not bullshit by definition, but it tends to lean in this direction, and consumers increasingly can tell the difference between the two.

While corporate sustainability's reputation for greenwashing has grown, so have environmental threats like climate change, demanding more than lip-service to respond to their severity. Can corporate actors evolve to confront environmental problems in a meaningful, material way?

At our consultancy, Seaborne, we think the answer is resoundingly yes. Not just because the climate crisis demands them to, but because it makes business sense. This might be something you’ve heard before. ‘Consider the double bottom line!’ This post is not about the elusive double bottom line. I’m not sure if we even believe it exists. What we do believe though is that there is a modern approach to sustainability work, or put broadly, companies doing ‘good,’ that can make for good marketing (read: good for business) while still being highly impactful. In order to explain why this is we first need to take a step back and explain how corporate sustainability got to this greenwashed nexus, and what specifically is broken about it.

What does ‘sustainability’ mean?

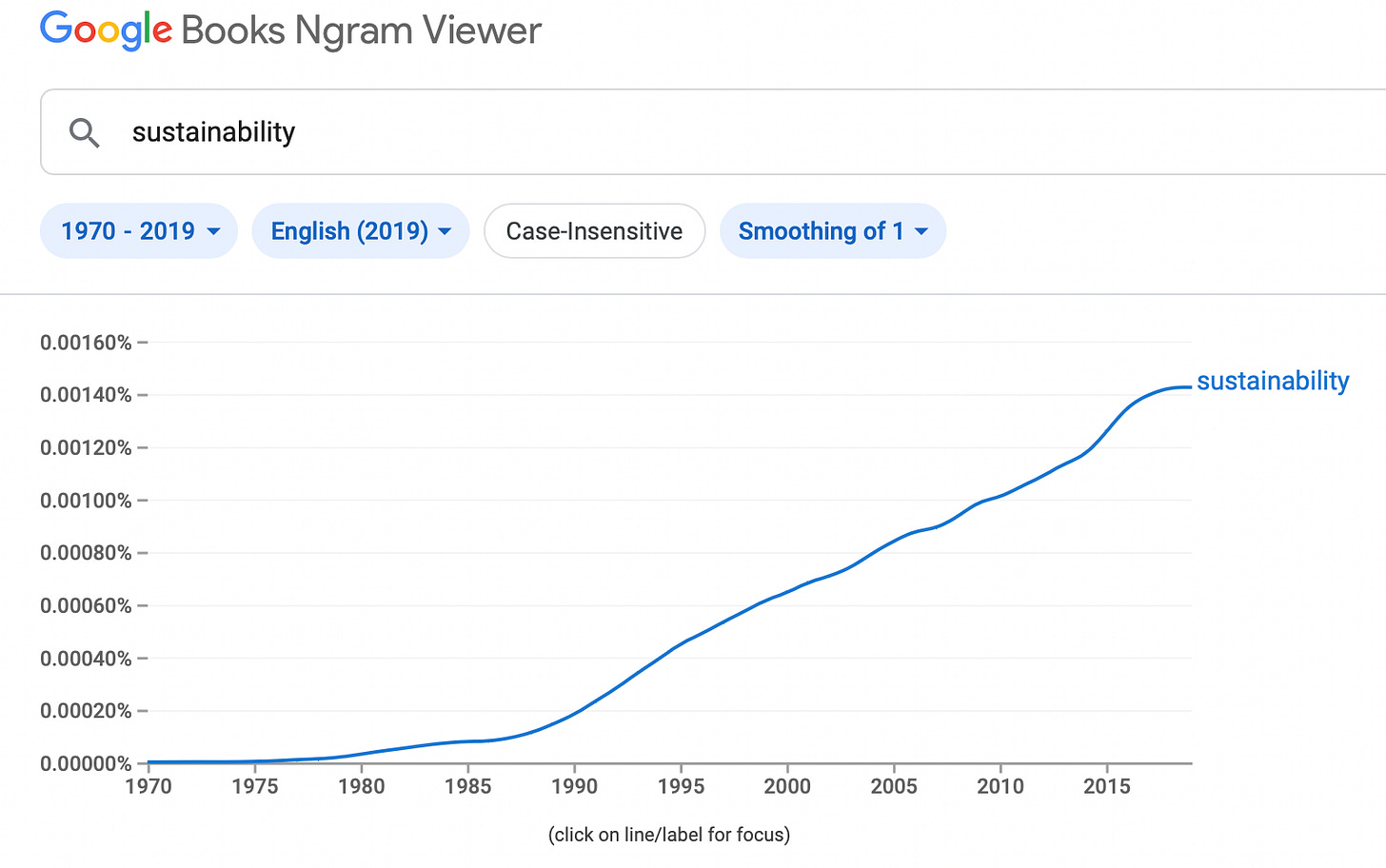

Let’s talk about term "sustainability." Before it was a corporate responsibility niche, the concept of sustainability emerged in the 1970s as an approach towards preserving earth's carrying capacity. If we were going to continue to rely heavily on earth's resources (something the oil crisis starkly revealed), we needed to find a way to do so that could support civilization into the distant future. Sustainability was used to describe the hypothetical balance that needed to be struck to accomplish this.

Because resource equilibrium is such an opaque end-state in a capitalist context, the activities that constituted ‘sustainable’ gradually took on a wide range of descriptions. By the 90s sustainable was a label that could equally apply to entire nations, cities, corporations, individuals and more. The current assumption is that any facet of life, be it architecture, food, or transportation, has a generally unsustainable basis of which a sustainable counterpart exists. Despite the term's quasi-material origins, sustainability has evolved into more of a broad sensibility than a boolean state. As a result, and even though it's used more than ever, not many people feel confident about what sustainability actually means.

Corporate sustainability suffers from the same ambiguousness. Is corporate sustainability an approach or an ideal? Is it a branding aesthetic? Is it a certifiable state with an end goal? Is it about climate change or plastic waste? Unfortunately there’s no single answer to any of these questions. At Seaborne we tend to think that the open-ended nature of sustainability is an opportunity just as much as it’s a challenge. In ambiguousness lies the ability to define our own approach that reclaims meaning.

When Greenwashing Works and Doesn’t

The problem is that the main incentive for pursuing corporate sustainability work is its ability to create more marketable products. Outside of sustainability efforts that are pursued based on compliance or regulation, much of this work is built around the idea of pandering to consumers' understanding of sustainability, something that’s notoriously variable.

Consumer products have attempted to make the most of a limited public understanding of the scientific basis for sustainability by using certification and labeling schemes which feign as a source of trust. While some of these attempts have been successful, they’ve generally led to the opposite of their desired effect — consumers end up putting too much trust in certifications and in the process further distance themselves from any significant understanding of their underlying claims. A survey about the USDA Organic certification showed that most consumers don’t know what it actually means, despite being the most common certification of its kind.

The superficial signaling function of certifications is not unrelated to the broader sustainability trend of greenwashing. When sustainability is a sensibility before it’s a concrete state, it’s something that’s easy to create broad aesthetic associations around. This is a phenomenon that brands with savvy marketing departments have been able to appeal to, often in dubious fashion.

Sustainability initiatives tend to be those that can be communicated visually or viscerally. This means that instead of thinking about sustainability as the process of minimizing the most materially negative impacts of a product, it tends to be about checking the boxes for what consumers expect from these initiatives. It’s been shown time and time again that consumers are willing to pay more for sustainable alternatives, so as long as a product can feign alignment with consumer expectations of sustainability, it can fetch a higher price tag.

The clear problem this dynamic presents is that consumer awareness is not always the best proxy for the relative importance of any given problem area. This is partially due to the entirely reasonable expectation that not everyone is privy to the complexities of sustainability. It's also due to the fact that what limited awareness consumers have is equally shaped by marketing just as much as it dictates this marketing.

What results is a process where businesses can take advantage of preconceived notions of sustainability, creating and marketing products that are only impactful by association, or in some scenarios actually make the underlying problem worse. Consider the recent movement to end the use of plastic straws, which became something of a meme several years ago following a viral video and crusading celebrities on social media. In response to this movement, Starbucks announced they would began to phase out the use of straws in exchange for redesigned plastic lids. The overall reduction in plastic volume (just compared to the straw + lid combo) was 9%. Starbucks gets to market these cups as a huge environmental win as consumers can make a clear visual association between unsustainable and sustainable, even though the difference between the two is marginal, and overall impact on the problem of plastic waste is negligible.

The reason why greenwashing has run amok is because it works if gone unchecked. When consumers aren’t met with transparency, they are forced to accept a brand's claims at face value. With more public concern over environmental pressures, consumers will choose products that posture as heeding these concerns, even if they aren't necessarily substantiated. Increasingly though, consumers do have legibility into the truthfulness of environmental claims from companies, whether that be through media, journalism, or increased educational levels. When this happens, it's been shown that consumers reserve negative judgements on greenwashing brands.

The trajectory of increased consumer legibility means something quite simple for brands who want to espouse their sustainable values. Sustainability will increasingly only be a competitive advantage for brands who actually walk the walk. Vice versa, brands that are caught greenwashing will face increasingly negative PR ramifications. Consider Voiz, a sustainability review database sourced from college students, as an example of the type of collective accountability that non-experts can leverage against companies who market sustainable products. More informally, social media is being used as a place for widely distributing critical discourse around sustainability and greenwashing.

Sustainability’s Subject Matter

It's clear that corporate sustainability initiatives will increasingly need to be viewed as credible. The question still remains though for what a credible program is focused on.

The subject matter of sustainability programs can take on many definitions relative to an individual company’s line of business. Typically sustainability consultants take stock of all the impacts a business could have in what’s called a materiality assessment. From here, depending on time, budget, and motivation, a company decides to tackle highest priority issues.

At least this is how it’s supposed to work. In reality other decision making criteria take precedence. Namely, and unsurprisingly, these conversations quickly derail from what is environmentally highest priority to what makes the most sense for business, which is to say, play off of consumer's preconceived notions. This begs the question: can you design sustainability programing that consumers understand that's not greenwashing?

One way to do this is by finding issues to focus on that balance being impactful and resonant with consumers. In our experience at Seaborne, we think that the issue that fits this description in most circumstances is climate change. Considering its immediacy, how widespread corporate inaction on the issue is, and how anxious the general population tends to be about it, climate action has high viability as a major focus for sustainability efforts.

Of course, there are cases that can be made for other issues. Generally speaking, initiatives can appeal to any problem area if a company is good enough at communicating why what they are doing is important, thereby simultaneously creating and appealing to the resonance of a given issue. Patagonia’s brand of CSR is famously good at achieving this. They have gone as far to create an entire outdoor lifestyle that is synonymous with conservation just as much as it is recreation. When you buy into Patagonia products you buy into their surrounding lifestyle and sustainability agendas, even if this means protecting things and places that many consumers will never even set eye on themselves.

A different interpretation of issue prioritization is modeled by brands like Seed and Humankind, which both focus on eliminating single use plastics from their product line. The issue of excessive plastic waste is of increasing concern and legibility for many in the US, thus making it a good starting point for a sustainability initiative. Both brands confront the issue of plastic waste by eliminating all non-biodegradable plastics from their product line and offering a refillable glass container subscription service. Humankind also offers a ‘plastic-offset’ program which supports ocean plastic removal efforts.

While there is no universal prescription for how a company might choose issues to focus on, companies like Patagonia, Seed, and Humankind show that all successful sustainability programs aim to ultimately be substantive. This is to say, they equally weigh resonance and effectiveness.

Towards a Substantive Sustainability

What we at Seaborne call substantive sustainability is any initiative that finds a balance between being highly effective and highly resonant. Effectiveness is measured in both how impactful and how credible said initiative is. Resonance, on the other hand, is measured in how legible and engaging said initiative is.

When an initiative is highly effective, yet not resonant, it suffers from not being very marketable. Consider a hypothetical corporate sustainability program that targets business flights. As an emissions reductions strategy, management starts requiring stringent pre-approval for all flights. Furthermore, when it's absolutely necessary to fly somewhere, it must be done in economy class. Doing this decreases the entire company's footprint overnight by 25%, which amounts to thousands of tons of CO2 prevented from being emitted. When the marketing team reaches out to the sustainability team for any updates on new initiatives, the sustainability team excitedly relays their success with flight reductions. The marketing team struggles to turn the story of this win into a new campaign though. "We are flying slightly less, and not in business class" did not test well with consumers who weren't aware of flying's impact on climate change, nor were they empathetic to the sacrifice of flying in economy class the same way they did. The insignificant marketing boost the flight reduction strategy provided makes management question whether or not such an expensive and voluntary initiative is worth their time.

Alternatively, when an initiative is highly resonant yet not that effective, it might be classified as greenwashing. Consider a buzzy startup that diverts plastic waste from landfills to recycle it into gen-z friendly skateboards. After the company was branded and capitalized, stress testing revealed that the recycled plastic in the skateboards did not hold up well to skateboarding. In a last minute attempt to preserve the quality of the product, the team decided to use a hybrid blend of 40% post-consumer plastic and 60% virgin thermoplastics. Thanks to a successful influencer-led Instagram ad campaign the first batch of boards sell out virtually overnight. Several weeks later, the skateboard company strikes controversy after the 'EcoTok' community hears about their not-so-recycled recycled skateboards.

Both of these hypothetical scenarios exemplify why corporate sustainability has so often been viewed with skepticism. Achieving both effectiveness and resonance in a sustainability initiative can feel like striking a difficult balance. At Seaborne, our specialty is working with forward-facing companies to uncover this balance point.

To give a better sense of how we approach this work, in part two of this post we'll walk through what pursuing substantive sustainability in the context of climate change programming looks like. Subscribe to our newsletter to read this post when it goes live.