Managing is a Maker’s Skill

How we built a better creative studio by becoming our own project managers.

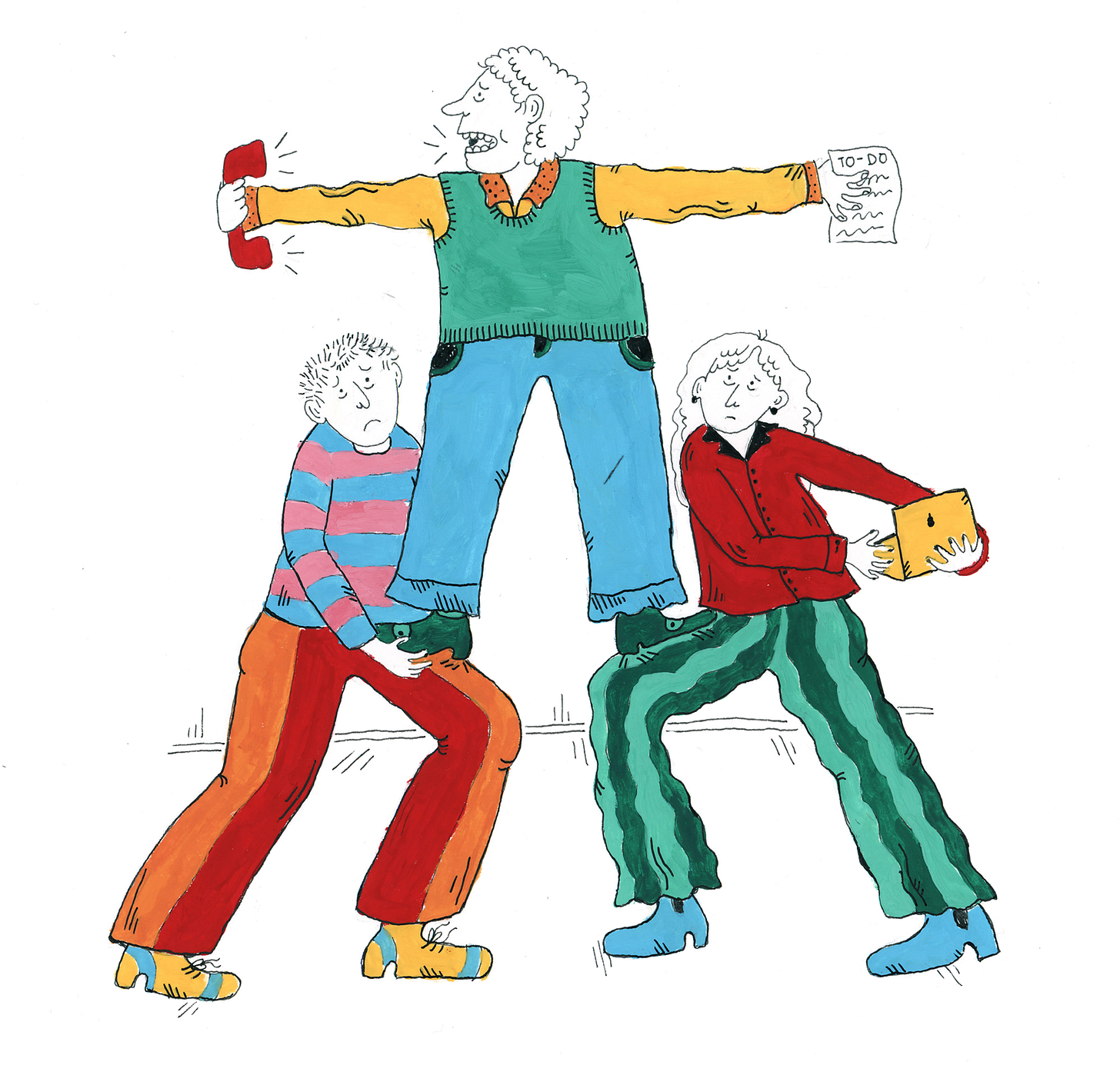

Most organizations are shaped like this:

Ours looks more like this:

We think of XXIX (and our sister studio Sanctuary Computer) as a circle whose strength comes from mutual support and self-reinforcing structures. In our mission to create the absolute best studio in which to be a designer or developer, all aspects of our organization are designed with this in mind, including our profit-share model, salary-setting practices, and decision-making process.

It's also a fundamental aspect of our approach to project management.

We don’t have project managers but we love project management

One of the first decisions we made when starting XXIX 10+ years ago was to not hire project managers but instead to train craftspeople to be highly effective project leaders. We consistently hear from our clients that our projects are the smoothest they’ve ever been part of: collaborative, stress-free, on-time, on-budget, and fun.

We recognized early on that building a separate management apparatus into our studio would introduce a tremendous amount of administration, cost, and politics to something that should be simple: empower creative people to communicate directly with the people they’re working with and give them the autonomy to decide what to do and how to do it.

All of this is not to say that we don’t believe in project management. On the contrary, we think it’s as important to the success of any project as “the work” itself.

We believe profoundly in craftspeople

Designers and developers are excellent problem-solvers. At Sanctuary and XXIX, we’ve also noticed that they’re often entrepreneurial, curious by nature, and excellent communicators. We’ve seen that the skills of a designer or developer are directly transferrable to other areas of our business.

As a teacher and founder, my biggest driver has always been to empower makers. I believe that ambitious craftspeople should learn skills and tools to amplify and empower others so that they can achieve bigger things for themselves — and set others up to do the same.

At our studio, we talk about building a culture of super-designers that can do anything. People rarely leave, but when they do, they're equipped to be founders, leaders at other organizations, or to run successful solo practices.

You don’t need to be a business person

We often say that managing is a maker’s skill. Most makers don’t have this skill because they’ve never been given the opportunity to develop it, not because they can’t! Strong communication, planning, and organization are core skills that all makers should grow and hone.

Our design and development teams were started as two independent studios by a designer and developer, respectively. If you had asked me ten years ago when I was starting XXIX if I was a good manager or had a natural ability to be an effective communicator in high-pressure situations, I would’ve said no. And I certainly didn't have any background in management or running a business. I had no other option than to learn these skills because there was nobody else to do it.

But even though I had no other choice, I also had a hunch that it would be more effective if I did it myself. It was only then that I realized that not only was I capable of doing this kind of work, but that learning it was an asset to myself, our projects, and our business. Sometimes I find it as rewarding as the design work itself.

Don't take my word for it! Here’s the man himself: “And you know what's interesting? The best managers out there are the great individual contributors who never, ever wanted to be a manager but decided they have to be a manager because no one else is going to be able to do as good a job as them.”

Class-stratification in creative workplaces

There’s a common and, in my opinion, pernicious stereotype that people are either creative or good at business. It carries with it the suggestion that the ’creative’ person needs the ‘business’ person managing them in order to be successful. This kind of manager-maker split creates a hierarchical class-system in an organization.

There’s often the excuse that managers are trying to protect the creatives from the harsh reality of numbers(!) and emails(!). Maybe the intention is well-meaning but, first, nobody wants to feel like they need saving, and second, they don’t need to be saved anyway!

Young, growing studios always see hiring project managers as the immediate solve for messy projects. How many times have you heard of a business “hiring an adult” to come in and hopefully (magically!) fix all these problems? Creatives don’t need parenting if they’re treated like smart, autonomous, self-actualized people.

Instead, at XXIX and Sanctuary, we aim to distribute both responsibility and reward equitably. We don’t believe in building an organization where administrative work is dumped on a staff subordinated to servicing the creative class, or one in which a management class reaps a disproportionate share of the reward.

We never lead with fear

A traditional project manager is dropped in between the client and creative teams, passing messages back and forth that they don’t have the domain expertise to evaluate themselves while often trying to align wildly different incentives. But the truth is, non-technical intermediaries have no actual ability to change the trajectory of a project.

Internally, the only real leverage a non-technical project manager has is fear: fear of an angry client on one side or an angry boss on the other. They have few tools to make the work go faster, be done more efficiently, or at higher quality; they can only try to drive the team harder. It should be no surprise when the creative team gets angry because they feel like they also have an internal client to satisfy.

Meanwhile, it’s in the client’s best interest to press the project manager to get more for less.

In this situation, a non-technical manager will often choose one of two paths of least resistance. They can promise something that may not be possible or advisable because they’re not able to assess those factors themself. Or, they can negotiate a compromise that leaves no one feeling satisfied because their primary incentive is to finish the project on-budget so they don’t get yelled at. It became obvious to us that neither of these paths prioritize producing the best quality work.

Our approach to project management

In our studio, every project team has a Project Lead. The Project Lead is the person on the project team responsible for ensuring that the project runs smoothly.

A Project Lead is someone who would describe themself as a designer or a developer. As such, they may also be an individual contributor on the project.

Establishing and documenting a repeatable process

Running a large, complex project with a bunch of stakeholders smoothly, efficiently, and with consistently great results is not easy. Fortunately, we have over ten years of practice and institutional knowledge to draw from.

We built out a process and set of tools based on those learnings that’s highly dependable and documented it thoroughly. This documentation is available to anyone in the organization, and we ask that Project Leads stick to the playbook but find their own style in doing so. This reduces the amount of project management work a Project Lead needs to do because they’re not starting from scratch each time.

Your job is the work you do, not the title you’re given

Importantly, this role isn’t something that a certain seniority level is obligated to do or rewarded with. In fact, it almost works in reverse:

Because we’ve detached role from responsibilities and rejected traditional industry titles that come with a lot of baggage, people are encouraged to reach for this opportunity when they feel ready. And because anyone can find the resources for how to do it and get the support they need to achieve it, they can truly decide for themselves when that happens. Upskilling into a leadership role is not gate-kept by traditional hierarchies (and thus, inherent bias), but available to all individuals at all levels.

Because the skills required to do this type of work map to our Skill Tree, taking on this responsibility will be reflected in a person’s salary. You can read more about how that works in an excellent article by Bre.

Getting buy-in

We know that people are here to design things and write code. If we don’t find the right balance with people’s core skills and interests, we run the real risk of burning people out. We try to avoid asking someone to be a Project Lead on back-to-back projects or two projects simultaneously.

Project management work can be hard, it might be uncomfortable at first, and many technical people believe that they’re not suited to this kind of work after being told so for their entire career.

In reality, once they get used to the idea and gain some experience, we often hear that people find it extremely empowering to have direct say in the outcome of their projects and that they actually welcome the variety in their work.

None of this should be surprising! If you’re working on a project and the budget is running a little hot, the vibe of your whole team collectively feeling that pressure and figuring it out together is way different than a manager coming in and breathing down your neck to work faster.

What it means for our clients

Sometimes there’s a little initial hesitation from clients when they hear there’s no ‘project manager’ on their project. But that goes away pretty quickly when they see that we take project management seriously. Our Project Leads set the tone for how the project is going to run from the first day. The reality is that if the work is good and the project is smooth, our clients don’t really care about the title of the person who’s doing it.

Work aside, I also just wanted to say a quick note on how impressed we are with the XXIX team's process, organization, and vibe that y'all operate with. We're big fans of how y'all work, and paired with the quality of work you produce, makes this partnership about as good as it gets.

– Nicholas Samendinger, Director of Brand Design at Magic Leap

★★★★★ Hospitality

When we started XXIX, a lot of our first principles came from what we didn’t want to repeat from past work experiences. We were helping our clients do all these incredible new things in new ways and we realized that we’d never turned that same lens on our own industry. When we started taking a more iconoclastic view of these assumptions, we saw a lot of outdated thinking and conservatism.

One near-constant was an approach to project management that left projects in perpetual states of chaos: gaps in information, always operating reactively, misaligned expectations, and – the most damaging of all – adversarial client/agency relationships. Chaotic projects made us miserable, and also seemed completely unnecessary and avoidable.

At XXIX and Sanctuary, we solve problems by pulling up weeds by their roots. We realized early on that the real cause of this chaos is actually pretty simple: inserting extra layers of communication between two teams who are meant to be collaborating.

The first step in being truly hospitable to our clients was eliminating unnecessary layers of management and miscommunication.

Aligned incentives

Sometimes people talk about the work and working on the work. Everyone involved in a project, client and creative team, can probably agree that the more work being done (designs being finalized, lines of code being written) and the less working on the work (planning, organizing, emailing) the better for everyone.

Makers are there to make things — no one went to design school to learn to make spreadsheets. The client wants to spend as much of their budget on outcomes they can actually use, and as little on the process required to get to those outcomes as possible. Makers and clients have a shared incentive to minimize working on the work. By default, the two major groups required to successfully complete the project actually have the same goal!

Real collaboration

The only way to work in a truly collaborative way is to break down as many barriers between the client and the creative team, and have them solve problems together. There are no surprises in this kind of direct relationship: everyone understands how we got to the place we’re in because we arrived there together.

As a result, never once have we had a project that looks like the client relationships that are so common at most agencies: reviews where the work was completely off the mark, the kind of “make-the-logo-bigger feedback” that designers hate, relationships where the project team constantly complains about how bad a client is or that they “don't get design”.

More efficient budgets

This puts the project manager in a sticky position, though: their job depends on them having enough working on the work to do. They’re actually disincentivized to make things too efficient.

This sounds a bit cynical – I don’t think most project managers actively seek to create job security by making more work for themselves or siloing information – but I do think it means they’re inserted into processes that could and should run without intermediaries being involved.

We don’t believe that simply moving information between parties or organizing work that should’ve been organized to begin with is something that our clients should be paying for.

Our business plan is quality

Ultimately, none of the above philosophy matters if our work isn’t good. I'll tell you why they're inseparable, though.

For the first five years of XXIX’s existence, I thought doing the best work was a matter of driving myself (and our team, probably) as hard as I could. There’s no doubt that some sweat is required when you’re starting out, but it only lasted up until I had an anxiety attack so severe that it put me in bed for three days while my partner was left to run the studio alone.

This was a transformative episode because I realized that you can’t force good work to happen; the best you can do is create the right conditions. It’s also when I learned a really important secret:

There’s one – and only one – way to do the best work: to care a lot. Education and training don’t make people care. You can’t scare people into caring, or pay them to care. You can’t even inspire them into caring. The only way to get people to truly care is to give them autonomy, respect, and real ownership over the work they do.

Jacob Heftmann (jacob@xxix.co) is a designer and the founder of XXIX.

Thank you to Hugh and Sam for their invaluable feedback; Simone and Elie for reading early drafts; Bre and Alicia for contributing key ideas I referenced; and Georgia Oldham for the illustrations; and the whole garden3d family for building a really nice studio environment for us to co-inhabit